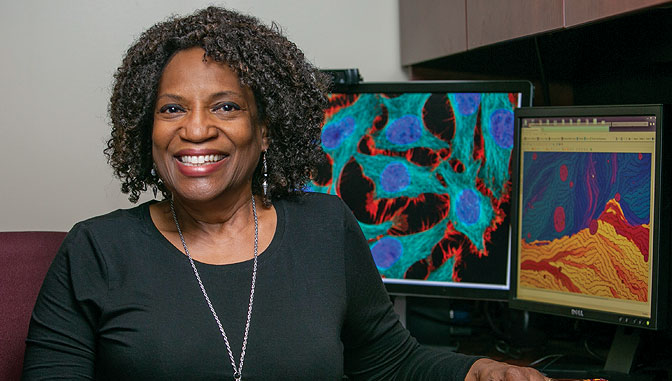

Q&A With Dale Emeagwali

What led you to your position as program director at Excelsior College?

For two decades, I was a full-time scientific researcher at institutions that included the National Institutes of Health and the Uniformed Services University of Health Sciences. From 1978 to 1996, I conducted full-time research in the fields of microbiology, virology, molecular biology, cell biology, and biochemistry. My contributions to molecular biology earned me the 1996 Scientist of the Year Award from the United States’ National Technical Association and inclusion in the “International Who’s Who in Medicine” and “Who’s Who in the World.”

I came to Excelsior College after three decades across five states in places including the University of Michigan Medical Center, Georgetown University School of Medicine, University of Wyoming, and University of Minnesota. I came to Excelsior College because I was looking for a new challenge, a new career path, and a new city.

What drew you to the natural sciences?

I thought about becoming a medical doctor but knew that I could not deal with blood and guts. For that reason, I studied microbiology at the Georgetown University School of Medicine and I conducted research at the National Institute of Allergies and Infectious Diseases at the National Institutes of Health.

What do you enjoy about teaching online courses?

Online courses break the barriers of space and time. I teach students worldwide, rather than those in a small classroom. My goal is to inspire deep thinking and dialogue and make my material come alive.

What career opportunities does a degree in the natural sciences offer?

I used my degree in the biological sciences to conduct research at the National Institutes of Health and teach at the University of Minnesota, and manage others at Excelsior College. As a researcher, my quest was to make discoveries that will improve the lives of others.

I expect my students at Excelsior College to become medical sales representatives, nanotechnologists, or science writers. Some become physician assistants, forensic scientists, or health care scientists.

What is your teaching philosophy?

I want to change the mindset of my students from cookbook biology to inquiry science, and I want to help them see the connections between textbook knowledge and the real world.

I taught students that they must be at the frontier of medical knowledge before they can discover the cure for cancer. I teach that as a discoverer, they will see the unseen, understand the misunderstood, and stand on the shoulders of earlier discoverers.

What challenges are involved with teaching STEM subjects?

The challenge is to build a stronger America through science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM). We conquer that challenge by thinking outside of the box. The primary goal of science education is to increase the nation’s intellectual capital and move humanity forward. The grand challenge of science education is to concretize this abstract goal by connecting it with students so science will become compelling, interesting, and visible.

What is your research philosophy?

In science and technology, a researcher’s goal is to discover or invent, and both are the act of seeing something previously unseen. At its core, my 35-year-long journey to the terra incognita of medical knowledge was a search for the cure for something previously uncured.

I discovered a type of protein that was previously thought to exist only in animal cells. Interestingly, since my discovery, it has been shown that bacterial cells even have genes in them that are analogous to human cancer genes.

In the field of virology, I demonstrated the existence of overlapping genes in a small DNA virus. This phenomenon is now widely accepted as a process for many organisms. In cancer research, I showed that cancer gene expression could be inhibited by the use of tiny pieces of nucleotides. There are now some cancers being treated with this technique and more clinical trials are ongoing.

The body of knowledge that defines biology is not narrow and specialized. On the contrary, it is broad and deep, expansive and encompassing. I take my students to the frontier of knowledge and sometimes into its terra incognita. I focus on what’s most significant in biology. That frontier is not static, but is ever evolving with each discovery that — hopefully — enhances the well-being of humanity.

What motivates you as a natural scientist?

Science education is, in part, about making an invisible equation of mathematics and law of physics visible so that students can appreciate and be inspired by it. At its core, scientific knowledge connects our children to their future and gives them the wisdom needed to raise their children.

A long time ago, a man once asked his children, “If you had a choice between the clay of wisdom or a bag of gold, which would you choose?” “The bag of gold, the bag of gold,” the naive children cried, not realizing that wisdom had the potential to earn them many more bags of gold in the future.

The wealth of the future is derived from developing intellectual capital — the clay of wisdom — that science education can give and that will make America stronger. We expand the story of science to enable our students to become a part of the story, as well as a witness.

My vision for science education is to tap into the creativity and innovation of our students — the people who have the potential to become job creators, instead of job seekers.