When You Aren’t Who You Think You Are

Genealogical professionals approach and solve difficult identity inquiries by thoroughly dissecting, analyzing, and reassembling complex genealogical problems. They gather evidence, evaluate and analyze records, and report the findings of these problems. As the following three examples illustrate, there can be surprising applications of genealogical approaches. Lessons from this sort of casework often show how life-changing proving one’s identity – in the sense of who they are and what they’ve experienced – can be.

WHAT’S IN A NAME? LAWRENCE SELLS FORD HATFIELD FINDS OUT

RESEARCH QUESTION: Is there a better way to learn your biological father’s identity?

OUTCOME: The discovery of a truth comes at a price – for everyone

Lawrence “Larry” Sells Hatfield, the eldest of a large family in Indiana, was headed to college for engineering when he requested a copy of his birth certificate. When it arrived, the teenager learned an unexpected truth: the father listed on his birth certificate was a complete stranger. Larry was not a Hatfield; he was a Ford. The man he’d called “father” his whole life was a step-father and his many siblings were only half-siblings. His biological father died of the Spanish flu in boot camp in 1917. His widowed mother, with infant Larry, remarried soon after.

Larry was furious that his mother had lied to him his entire life. In a rage, he threw away a full scholarship and broke all ties with the man he knew as his father. Larry married, served in World War II, raised four children, and found a career on the floor of an Indiana factory.

Larry’s anger is not unusual, but he may have made better decisions had his family handled the information differently. The reveal of his true identity shattered his trust, but did that need to be the case?

Today, genealogists know we have four kinds of family: a genetic family (where DNA contributions from certain ancestors eventually disappear); a genealogical family (everyone who is your ancestor); a social family (including anyone you welcome into your life); and, finally, a legal family (defined by law, as in adoption or disinheritance). There is now a fifth kind of family for people who have organ transplants and share the donor’s DNA. For example, a sister who receives her brother’s kidney will now test as both female and male, so this leads to a new definition of self.

Identity is defined and embraced by the individual. Is it ethical to conceal the truth as in Larry’s case? Do fostered or adopted children have the right to know their origins?

MIRIAM PERLSTEIN LOWY, SABINOV HOLOCAUST SURVIVOR, SHARES HER PAST

RESEARCH QUESTION: Was her story true?

OUTCOME: Finding sources that contain evidence that meets the standard for truth

Miriam Perlstein Lowy survived the Holocaust and told her story to her son only once when he was 18. He wrote it out in Hebrew and never forgot. Forty years later, an elderly Miriam was plagued by dementia and began living her life backward. Knowing her history, he understood why his mother mistook him for his father, then later hated him as an SS officer trying to imprison her. Ultimately, she cried about her older sister, torn from the family and sent to entertain the troops, never to return.

His reluctant retelling of the story captured the attention of a screenwriter. But was it true? As important as never forgetting is not perpetuating a fraud. Could the incredible facts be proven and documented?

Years later the answer is a resounding “Yes!” Genealogical research reveals extraordinary evidence. Survivors from the 100 Jewish families of Sabinov, Slovakia, were few but fierce. At least nine made it to New York City by the late 1950s. Six of the nine made recorded testimonies about their experiences. Each Holocaust witness was instructed to tell only their own story, yet details in their testimonies helped corroborate information in Miriam’s story.

Florence Reimer was Miriam’s best friend after the war. In her testimony, Reimer tells that she was born in America and recounts her father’s fateful decision to return to Slovakia in the 1930s to be with his parents. Her father, mother, and teenaged brother were killed, but she was exempt from the March 1942 “transport” of young, unmarried Jewish women because the government did not dare mistreat an American.

Dr. Eugene Schnitzer and his wife Serena survived the war in Sabinov with an “exception” that he was a doctor. They kept his niece and his in-laws in a large armoire in the living room under the noses of the authorities. He once took niece Vera out for a walk, but never again. The townspeople, once so friendly, knew Vera was not supposed to be there and their stares were hostile.

Lt. Joseph Schnitzer and his wife were transported in May 1942. Joseph’s relative bribed many people and chased the train for 15 miles before catching it. The car doors were opened and Schnitzer was called to come out. He refused to leave because he felt everyone should be allowed to go home. At the Polish border, Schnitzer fed hundreds of people during a wait for a new train to the concentration camp Sobibor. He fired up an abandoned bakery and scrounged supplies. Schnitzer’s Bakery on the show “Seinfeld” was a real place owned by the real Joseph Schnitzer.

Every detail in Miriam’s story—from jumping from the train headed to Auschwitz, eluding capture for almost two years, escaping death when the camp was liberated as she faced execution, hiding in the snowy Tatra Mountains, and hating the people of Sabinov who stole her family home and shunned her when she returned—can be documented. Research into independent testimonies such as those above, the log books of Auschwitz, a census of Sabinov, and the tattered photos hidden for decades say it is so. As a result, her story meets the genealogical proof standard of truth and will soon be told through a book, a screenplay, and eventually a film.

A NEW LOOK AT AN OLD CASE: JANE DOE NH 1971

RESEARCH QUESTION: Who is she?

OUTCOME: Genetic genealogy will resolve the mystery

A young hunter found Jane Doe NH 1971, as she came to be called, a long time too late. He stirred the woodpile with his rifle and ran to the police station when her sightless eyes met his. Since New Hampshire did not have a medical examiner in 1971, the go-to doctor came from Massachusetts to preside over the recovery in the chilly October rain.

Dr. George Katsas said Jane Doe was 16 to 35 in age, probably in the older range. He wrote down no cause of death in the first autopsy, and inexplicably took home her mandible and maxilla. She had no ID, so the police placed an ad in the local newspaper. Many people came forward, searching for their lost daughters, sisters, or wives. Those missing women were eventually found, but no one claimed Jane Doe NH 1971.

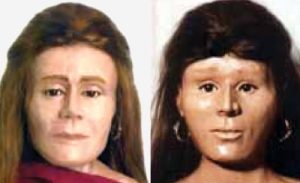

Decades later, the technology exists to date her age to within six months. This requires counting rings of cementum formed around her teeth, but that part of her skull is not with her remains. Height and weight estimates for Americans have also been updated from the long-used Depression-era figures, but people reading Jane Doe’s description still envision a young runaway or prostitute. She was almost certainly a housewife in her 30s, robbed of her future. Two reconstruction artists created what her face may have looked like, based on her skull, but the renderings could not be more different.

When all else fails, genetic genealogy can lead to a definitive answer. DNA is not just for exclusion any more. With basic skills, a researcher can use autosomal DNA to name the remains of soldiers missing in action or killed in action by matching the primary next of kin. It can and will also name Jane Doe NH 1971 and the tens of thousands of unknown dead who await the return of their identities. A non-disclosure ends the story here, for now. More than five of these cases have been solved in the last few years and all road signs point to genetic genealogy becoming a necessary step in cold case identifications in the future.